…….photos and reflections on cities, buildings and the way we live. This sub-home page displays posts on these subjects, starting from the most recent. If you would like to read posts organized by place or subject, use the drop-down menu in the menu bar above.

We said goodbye to our Road Scholar group on Sunday night, and on Monday morning we caught a local bus that would take us to a train in Nunspeet, which would take us to another train in Amersfoort, which would deliver us to the Central Station in Amsterdam. The trip was smooth and efficient, and we were afoot in the rain in Amsterdam within 1-1/2 hours. We walked 30 minutes to our AirBnB’s check-in office, took a cab to our Bickersgracht apartments and were greeted by Katie & Kyle, Russell & Monica, all ready to begin the Amsterdam adventure.

There is a special car on the train for bikes–and we were told you have to pay a full fare for your bike to take it along.

The trains were fast, with minimum transfer time. Two carloads of school children rode the train, apparently on a school trip to Amsterdam. We never saw a school bus in the Netherlands–bike and bus are the way school kids travel.

Canal views are everywhere, this one at dusk (which is currently 9:30 PM at this northern latitude).

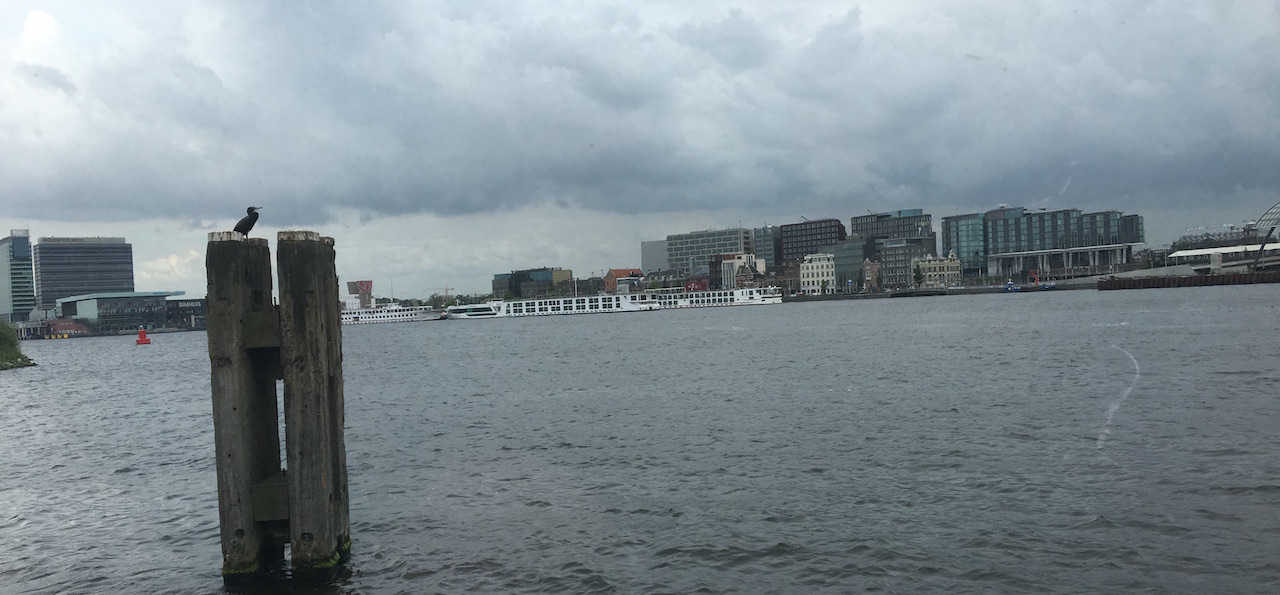

Amsterdam is wondrous. It is a hub of 21st century human activity taking place in buildings old and new. As the densest city in the EU, it feels remarkably spacious because of the generous amounts of public space—largely canals—and preponderance of 4 and 5 story buildings. The interplay of buildings and canals create magical vistas every couple blocks. It is often referred to as the “Venice of the North”, but unlike Venice, tourism is not its life blood, and in fact Amsterdammers are studying ways to reduce tourists’ impact on their daily lives, which may include ways to discourage tourists.

The only city as inextricably linked with water that I know, other than Venice, is Vancouver. Vancouver may be the most beautiful city in the world, but Amsterdam is a more complete city—it has beauty, brains, dynamism, history and character.

For all the density and bustle, Amsterdam streets feel comfy, not crowded, and the predominance of bicycles rather than cars brings a calmness, a quietude unknown to other large modern cities. The

Dutch disposition may play a role in this as well. Loud conversations, shouting, and horn honking appear to be discouraged in favor of minimal gestures and a few mild words. Drunken group singing on Friday and Saturday nights is the one exception we noted to the general quietude.

There is a multitude of sights to visit in Amsterdam, including museums, boat tours, and architectural monuments. The thing we enjoy most, though, is just being in the street, experiencing the people and life of the city.

The sea defines the Dutch. The earliest occupants of “The Lowlands” were seafarers who owed their survival to the sea. Later, they would band together to build dikes to move back the sea edge and establish more land to farm. Later still, they would use their business acumen and individual initiative to master shipbuilding and international sea trade. And through this all, they would organize collectively to battle the North Sea’s relentless battering of their fragile dike system.

It is a fundamental fact that 50% of the Netherlands is below sea level or at sea level and subject to high tide flooding. Prime, fertile areas of Holland are as much as 20 m. below sea level. Living safely below sea level requires vigilance, engineering, massive electric pumps and lots of money—$330 per year per Dutch resident ($5.6 billion). Few argue or complain about the expenditure, and the science and impact of global warming is not a debate here.

Amsterdam buildings and boats line the canals. Flooding in Amsterdam is not anticipated to be as much of a problem due to the many gates, pumps and and other flood control measures in place.

One benefit of this ages-old battle against the sea is the Dutch now lead the world in hydrological engineering and work world-wide to help other nations solve flood control problems. They also are leaders in responding to at-sea emergencies, salvaging damaged or sunken ships, and building custom ships.

The Dutch will need to keep expanding their expertise in the 21st century as they face rising seas.

More Dutch engineering: almost all bridges are draw bridges to permit boat and barge navigation. Some are hinged and swing open like a gate as shown here.

Dikes will need to be bolstered and raised, of course; an even more widespread threat will come from the Rhine, Waal, IJ and other major rivers flowing through the Netherlands. As the sea rises, they will rise as well. Couple that with more intense rains in the Alps, and the Dutch will need to build new levees along the length of most rivers to keep flooding at bay.

The $330 per year per resident is likely to go up significantly, the price of staying alive. The Dutch have always been up to the challenge.

Amsterdam features a special segment of Dutch engineering. To build a city in a swamp, the Dutch had to figure out a way to keep buildings upright.

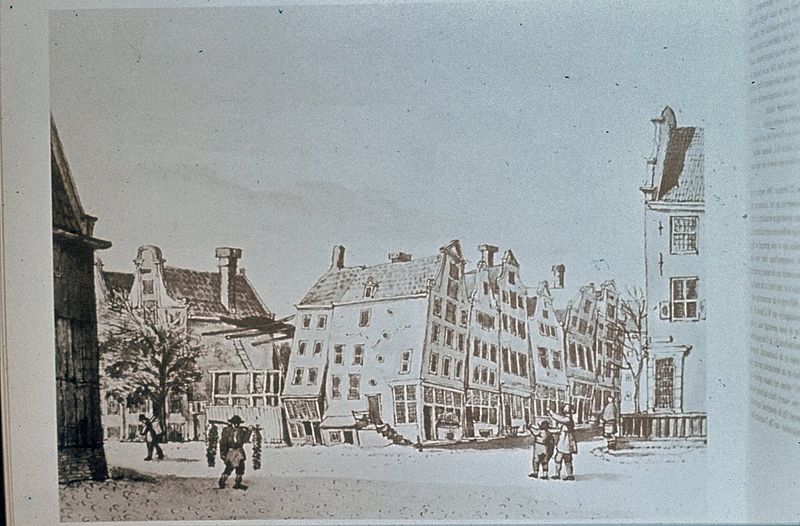

Initially, they built one and two story wood buildings on cowhides. The cowhides spread the light loads enough to keep the houses mostly afloat—an improvised raft. This was not a long-lasting solution, both because of the limited life of wet cowhide and potential fire damage to the wood building above. After much of Amsterdam was destroyed by fire in 1452, the ruling power declared that all new structures had to be built of brick. This required new means to support the additional weight: wood piles.

Until recently, most Amsterdam buildings have been built on wooden piles. Amsterdam’s water table hovers about 1 m. below the surface, rising or falling with rain and drought. The nearest layer of bearing soil is a stria of sand 12 m. below. To reach this, Amsterdammers drove wood poles—generally pine or spruce—through peat and marl. The Centraal Train Station, for example, was built in the late 1800’s using over 8,000 wood piles. As long as the piles stay wet continuously, they do not rot. If the tops of piles extends above the water table and are subject to wet/dry cycles, however, they will eventually rot, causing a difficult structural problem.

Modern building methods use steel or concrete piles and extend down to a second, more substantial, sand layer about 25 m. below the surface. This supports the taller steel and glass buildings one sees along the IJ.

A related engineering problem has been tunnel-boring for underground portions of Amsterdam’s train system. A major north-south expansion of the train system, begun in 2002, requires a 7 km tunnel under the Central Station and the IJ. The challenges of keeping out the water, supporting train weight and avoiding the pin cushion of pilings from existing buildings is immense. In fact, the tunnel–designed by a German company–ran into problems in 2008 and is still not open, though the first train should run in 2017. Here’s what happened:

On 19 June 2008, during the construction of the underground station on the Vijzelgracht, a leak in the concrete wall caused water and sand to flow into the pit. This caused tremors in the wooden piles under the houses nearby, making some houses sink 15 cm into the ground. Residents had to be evacuated. The work was stopped immediately and repairs made. Then, on 9 September 2008, construction started again. The next day, more houses sank, this time 20 cm within the hour. Cracks started to appear in the walls and windows, and doors wouldn’t budge. The row of 300-year-old houses, known as the Weavers Houses, became suddenly uninhabitable.

This is why Dutch architects and engineers lie awake in the middle of the night!

Where are the traffic jams in Amsterdam? Amsterdam is the densest city in the European union, the financial capital of the Netherlands and part of an extended metropolis of 7 million people. Amsterdam proper has about 800,000 inhabitants—and 1.2 million bikes. There’s a good reason many people have more than one bike—the kid transport you use to take your two toddlers to daycare or haul groceries from the store may be a tough pedal to your corporate job in Centraal.

Amsterdammers do not ride expensive bikes. They ride heavy, durable work horse types, black, single-geared, with coaster brakes or hand brakes. Since 80,000 bikes are stolen each year, there’s little pride of possession and most residents use 2 locks to secure a bike. They also ride in the rain, cold, and wind, given Amsterdam’s English-style climate, and plain black bikes can be dirty or rusty without anyone caring too much.

It’s amazing how tiny a bike footprint is compared to a car’s. A bike with one or two occupants may cover 10 SF, whereas a compact car with 1 occupant will cover 50 SF. A bike leaves lots of room for others. Plus bikes are more nimble at intersections—the locus of most congestion—, meaning they can stack more densely and disperse more quickly.

On main streets, pedestrian, bike and car paths are clearly defined. On minor streets, everyone shares, although bikes generally have the right of way.

This isn’t to suggest that car-driving in Amsterdam isn’t a frustrating experience. It must be, given the many road and right-of-way restrictions. It is just to say that a city that gives equal weight to pedestrians, cyclists, trams and cars, and is dense enough to keep trip distances short, does not experience congestion like cities that prioritize only cars. As a native Amsterdammer, Eva, said, “Why would I have a car when the streets are narrow and it’s hard to find a parking space and I can get everywhere on my bike?”

Remarkably, in our brief time in Amsterdam, we have seen no collisions or crashes. Bikes, walkers, trams, work vehicles and cars create a melee’ of activity on Amsterdam’s narrow streets and free-lancing the rules, especially by cyclists, is fairly common. Yet there appear to be few “incidents.” It took us four days to see a middle finger issued in response to road behavior—by a motor-vehicle driver, of course. This may be partly a tribute to Dutch tolerance and collectivism, but it seems to be mostly due to controlled speeds, alert action and agreement on the advantages of road-sharing.

Amsterdam has one more distinct advantage over a city like Atlanta: terrain. Amsterdam is generally listed as 1 m. below sea level, with the highest point in the city being about 17 m. above sea level, but in fact most of the city shows elevation differentials of no more than 4 m. That is FLAT! And it means anyone can ride a bike, and bike gearing is unnecessary for most situations.