One of the great joys of travel is the unexpected encounter, the unscripted moment that betrays the itinerary. As our walk on the Lake Manyara salt flats continued, we spotted a brush-fence perimeter 1000 meters distant. We could see a herder with some goats in the vicinity, and our day guide (a local guide, assigned by our lodge) suggested we could walk in that direction.

We walk toward the boma in the distance.

Our host, who invited us to see his boma

We approached the herder and our day guide offered greetings and small talk in Swahili, and asked if we might inspect the brush-fence perimeter. The man, a Barbaig, offered to show us not only the brush fence but his whole boma.

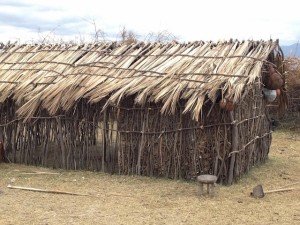

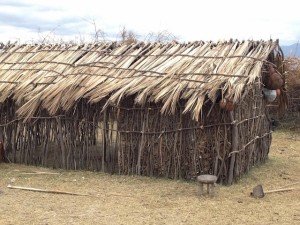

The Barbaig tribe migrated into northern Tanzania a few centuries before the Maasai. They came from the Sudan/Ethiopian plains, as did the Maasai, and they share common ancestry with the Maasai. They are pastoral (herders) like the Maasai and share many physical traits as well as dwelling design and village structure. The basic family living structure is a “boma,” which is a round brush- or stone-fenced enclosure, sized to contain the family’s dwelling as well as their herds.

The boma gate is a thornbush pushed to the side for the daytime. Our day guide, a Maasai, is in blue, between Chagamba and Mika.

We followed the man to the enclosure and he led is through the gate, which was a thorn tree thrown to the side. The enclosure was circular, about 50 meters in diameter, and was partitioned into a corral for cattle, a corral for sheep and goats, and a living area with simple mud structures for family quarters.

Typical boma plan (internet photo)

We meet the family. The main hut is in the background.

His daughter watches thoughtfully.

The man’s wife and 2 children came out to greet us, shyly. They allowed us to peak into their living quarters–cramped, dark, low–and soon two women from nearby bomas joined us. We asked questions, with our day guide, as well as Chagamba and Mika, interpreting. Their water source was a spring about 3 km away. They used donkeys to carry water in 5 gal. buckets. The wife and 2 daughters slept in the house, the husband in a shed about 10 meters apart. We learned that it is not polite to ask a man how many cows or goats he has, though this man had a good deal of both–enough to have another wife in a different village. They welcomed us to take pictures.

Dad’s sleeping accommodations are part of the shed, 10 meters from the main hut.

We offered the man a tip as we were leaving, 10,000 shillings, a generous amount. “What about my wife?” he asked. Caught unawares, we dug in our pockets and came up with another 5,000 shillings and offered it to his wife. “And the neighbors?” he asked? He was

Water transport system. A spring is about 3 km away.

a good businessman! Our guide intervened at that point and we wandered back into the open land and headed back toward the lodge. We felt very privileged to have spent time with a Barbaig family and seen a boma from the inside. Our day guide confessed that he had never done this before.

Detail of the wattle. Cattle dung and mud are mixed together to form an adobe-like material.

Chagamba speaks with the family and interprets for us. Swahili is the common tongue, though not the native Barbaig or Maasai language.